The nation of visionaries

Peru, 2016

An historical decision was taken in Soledad, a small village of Rio Santiago, 1,500 km north-east of the Peruvian capital Lima. Representatives of over 100 communities of the indigenous Wampis people announced the formation of the Autonomous Territorial Government of the Wampis Nation, the first of its kind in the whole Amazon, with its own constitution, parliament and executive organs. “We will still be Peruvian citizens”, -says one of their visionary leaders, Andres Noningo, 62, “but now we have our own government responsible for our own territory; This will enable us to protect ourselves from companies and politicians who only are able to see gold and oil in our rivers and forests.”

In Peru there has always been a mutual distrust between indigenous people and the government, as evidenced by the ‘massacre of Bagua’ in 2009: the approval of new laws, facilitating access to the indigenous lands for extractive industries, sparked protests, which ended in the killing of over 30 indigenous people and policemen. State concessions and recurrent hydropower projects are not the only threats to the Wampis territory: a rotten 40 year old oil pipeline of the state company Petroperu is leaking more and more each year, while illegal gold miners are on the verge of transforming this unspoiled land into another Peruvian nightmare like Madre de Dios.

Not all the dangers come from the outside. After decades of cultural homogeneization, a lot of the indigenous knowledge is at risk of being forgotten and the Constitution of the Wampis Nation aims at its preservation. It is a culture that reveals the deep attachment of this people to nature. For them, forests and mountains are sacred, hiding waterfalls where aspiring visionary warriors search for guidance during the ritual of Ayahuasca. Today visionary warriors have become ‘statesman’, setting a new precedent in the Amazon by forming an autonomous indigenous government. On the 20th of March 2017 the newborn nation will be presented to the Peruvian National Congress. A series of other indigenous groups is preparing similar initiatives and how the Peruvian state will respond to the Wampis’ self-declared autonomy may set an historic precedent.

A family fishes in the ‘quebrada’ Ayampis, one of the many tributaries of Rio Santiago. Wampis like to say that the forest is their supermarket. The rivers are key to daily life as a source of clean water and fish and there are no problems with food security in the region. Amazonian forests are nicknamed “the lungs of the planet” for their capacity for turning carbon dioxide into oxygen, mitigating climate change.

A lady walks on the North Peruvian Pipeline the 13km separating the community of Mayuriaga from the latest oil spill. The pipeline, which is long overdue to be replaced, connects the Tigre region, in north-eastern Peru, to the coast. Leaks and spills are frequent.

Children play football under heavy rain in the community of Soledad. The Wampis territory, roughly the size of Connecticut, is inhabited by 20,000 people. There are no roads and the two main rivers, Rio Santiago and Rio Morona (Kanus and Kankun respectively in the Wampis language), are the only access to trade and to the outer word.

A young person rest during a three day fasting in the forest before the ayahuasca ritual to become visionary warrior. Visions are essential to the culture of Wampis people, as explained by Andres Noningo, 62: “Our visionaries would spend up to three months in the forest. They taught us that every animal and tree are people just like us and have their guardians which protect them.”

View of Mayuriaga, the community situated on Rio Morona hosts 60 families. Due to the nearby oil spill the oil company is now distributing bottled water and food to the people affected by the spillage. The Mayuriaga community is in the process of asking for compensation for the contamination of territory fundamental to its survival.

A girl plays in the mountains above Soledad during a three day fasting in the forest. As a ritual it is necessary to spend several days in the the forest learning sacred songs and fasting before being introduced to ayahuasca. If during the ceremony they will achieve a vision, they will become visionary warriors.

The latest spill, in 2016, affected 30km of tributaries before seeping into the main river Morona, and affecting communities living downstream. The cleanup operation, still ongoing, is involving almost 500 people, and will take at least a year. Every piece of soil and vegetation which has been in contact with the crude oil has to be destroyed.

Boots used for working in the Mayuriaga Oil spill drying at the end of the day. “When the Peruvian government speaks about development, they mean the exploitation of our resources: gold, oil, wood. This threatens our livelihoods.”, -says Andrés Noningo, “that’s why we decided to form our autonomous government, to ensure a good life also for future generations.”

Forest damaged by the oil spill near Mayuriaga. Because of the multiple threats to their environment, Wampis were inspired to create the new government by the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, were driven by the multiple threats to their environment and aim to prevent its exploitation by the governments, companies and individuals.

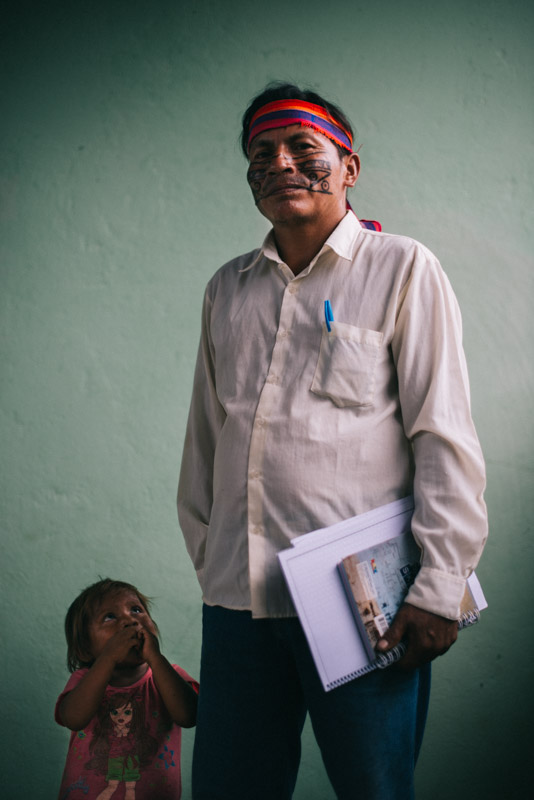

Kefren Graña, 45, a former teacher, is the Minister of education of the Wampis Nation. Today young people are confused and disorientated between the model of a consumer society learned at school and the traditional values taught by their parents. Kefren promotes the use of hallucinogenic plants fundamental to re-establish a connection with nature: “Ayahuasca, tobacco and toé are our university”.

Members of different communities of the Wampis Nation mapping the traditional use of territory along the meandering Morona river. Only parts of the land rights are recognized by Peruvian legislation. Ancestral uses, like hunting or vision seeking, are granted only by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which protects the right of indigenous peoples to own and manage their territories.

Arrival of the delegations in San Juan de Morona for the Assembly of the Nation Wampis. The travel, by foot and boat, from different parts of the territory can take up to 4 days. The constitution has 40 pages with detailed provisions on rights and duties of the government, the management of the territory and culture. The Wampis underline that self-determination doesn’t mean separatism – they remain Peruvians.

Leaders and members of the Wampis Parliament: Tercerp Gonzales Ana Maria, 46. Irunin de la comunidad de Guayabal (Rio Santiago).

Leaders and members of the Wampis Parliament: Segundo Sinley Tukup Wigui, 47, Ankuash. Presidente de Asociacion Nativa Ankuash.

Leaders and members of the Wampis Parliament: Elena (45) and Rebolio Garcia (52), Presidente of OSHDEM and Presidentesa des mujeres OSHDEM. Saphaja.

Leaders and members of the Wampis Parliament: Alejandro Wajai,52, Panguana.

Leaders and members of the Wampis Parliament: Lola Tuwiran Juhuo, 42, Galilea. Coordinator of Wampis Women (Fechorsa). Consejo de Savios de la Nation Wampis.

The perilous pongo – rapids – of Manseriche on Marañón river. In Quechua, Manseriche means ‘the frightening gorge’. The location inspired Werner Herzog’s movie Fitzcarraldo. A dam project has been looming on the upper Marañón. A series of 20 dams are already in advanced stages of planning. It has been estimated that the biggest, on the Manseriche, could flood 5,470 square km.

Land destroyed by gold mining along the waterway of the Quebrada Pastacillo. “We cultivated this land since the time of my grandfather,” says Rogelio Padilla, who used to farm the place. “But when illegal miners arrived they behaved as if the land was belonging to them.” When a forest that could sustain generations is destroyed, the loss is impossible to quantify.

Illegal miners extract gold from sediment on the Marañón river. Illegal gold mining is very prevalent in the region, where an estimated 20-120 grammes can be harvested in a day, worth between $600-$3,000 (£465-£2,320), a lot of money in this poor area. Aside from the destructive impact on the landscape, gold mining commonly involves the use of mercury, which leeches into the water and the food chain.

Moments during the discussion before the ‘peaceful’ action at the illegal goldmining site of Pastecillo. One of the key demands of the Wampis government is the power to patrol its territory to guarantee a quicker official intervention on illegal mining and logging than that by Peruvian state agencies.

150 Wampis warriors invaded the site of the illegal mine on the Pastacillo tributary to protest against the activities there and to expel illegal gold miners from their ancestral territory. Miners, who had been tipped off, hid the machines and suspended their work for a few days.

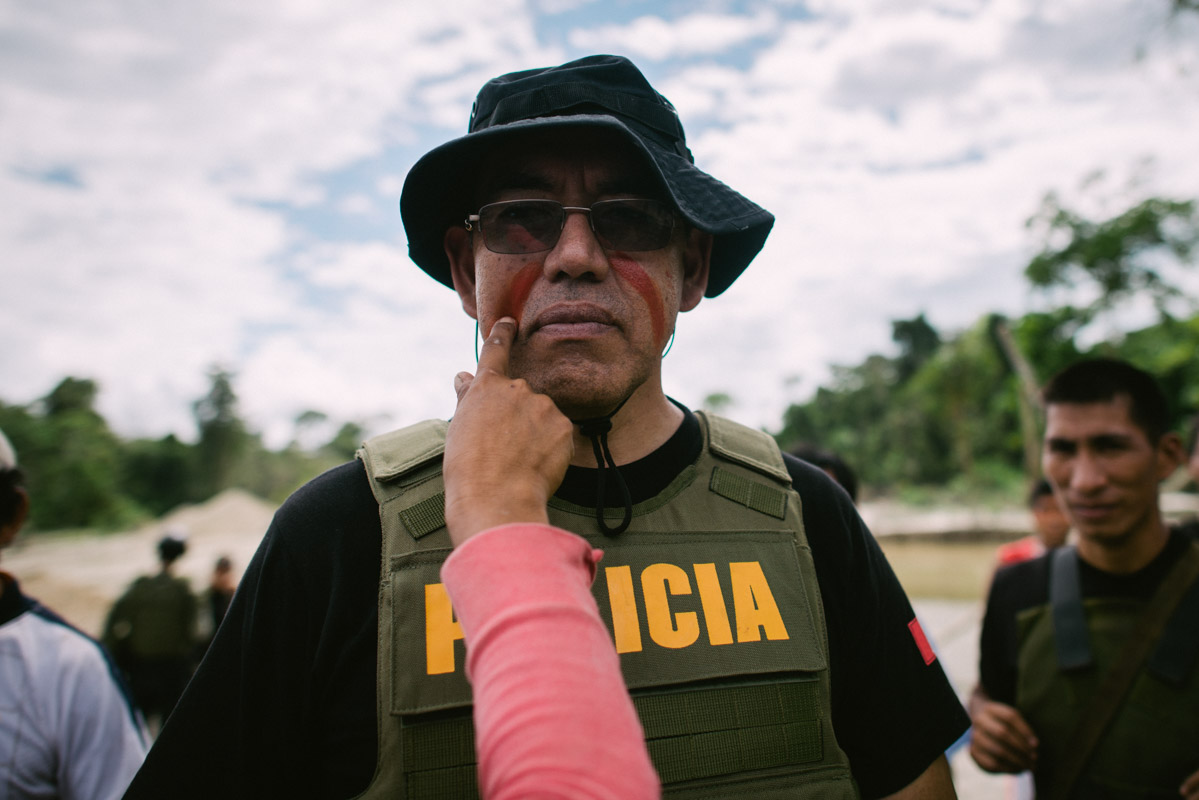

The chief of the police receives his warrior face painting during a protest along the Pastacillo tributary, as a sign he is an ally in the fight against illegal gold mining. The Peruvian government is engaged in a well advertised fight against illegal miners, which unfortunately seems to be ineffective.

Wampis protesters break mining equipment near the illegal mining site. In the basin of Rio Santiago river mining started in 2012 and there is fear that the situation, if not stopped, could quickly cause a major social and environmental crisis as happened in Madre de Dios in southern Peru.

Crosses at the Pumping Station 6, on the North Peruvian Pipeline, to remember policemen killed during the events of 2009 in Bagua. Following a set of laws facilitating access to their lands by the extractive industries. Wampis and Awahun people marched to Bagua, blocking the main road. In the clashes that followed, at least 34 people – 24 policemen and at least 10 civilians – died.

People searching for mobile connection in Soledad. After more than 50 community meetings and 15 general assemblies, in this remote village, on the 29th of November 2015, came to life the Autonomous Indigenous Government of the Wampis Nation. It was announced to the world through the first e-mail ever sent from Soledad.

A couple at the binational meeting in Ecuador. The Wampis’ desire to protect their way of life has been strengthened by what has happened to the Shuar people in neighbouring Ecuador, people of the same ethnic group as the Wampis. A major road accelerated the loss of Shuar identity: many people have forgot their native languages, and cattle farming and logging are more widespread.

A class in the secondary school in Soledad. School classes, taught in Spanish and in Wampis language, are a strong force of cultural homogenisation, teaching values of a consumeristic society. By contrast Wampis people grow up with an intimate connection with nature and a deep faith that the natural world will provide for all their needs. Higher education is possible only in far away cities.

Lunch break during work in a chackra. Chakras are ancestral plots of land belonging to the community but temporarily used by individual families. During the day a family usually spends time cultivating its chakra. Common harvests include banana and yucca, which make up the core of the Wampis’ diet. Little cacao plantations are becoming common, allowing people to sell some of their crop.

A busy day in the town of La Poza on Rio Santiago. Situated few hours of navigation away from Santa Maria della Nieva, the only road access to Rio Santiago, the town is booming as a frontier place. Here indigenous people can exchange their money with products sold by settlers and miners can sell their gold.

A club in La Poza. The town has a thriving nightlife where miners can easily spend their wage in beers. HIV and prostitution are reported as emerging problems.

A girl looks at the sunrise during the ritual to become a visionary warrior. “Our ancestors noticed that the animals speak and even the earth moves and they asked where do these animals come from? What is the origin of the air we breathe, who looks after the trees? What is the origin of life?”, -tells Andres Noningo, member of the Council of the Elders of the Wampis nation.

Teenagers rest in a tambo, a construction quickly made with leaves in the forest. “By talking to nature” -continues Andres Noningo, “our ancestors were able to teach us where the animals live, where they reproduce, which lands are fertile and which are not, where we should make a farm and how to hunt with respect, using our anent, sacred songs that ensure we treat all living beings with dignity.

Teenagers drinking and vomiting ayauascha. Incited by their families they will have to drink 20 or more litres of liquid to increase the chances of acquiring a vision and therefore becoming a visionary warrior. Ayahuasca is used as an hallucinogenic substance to obtain visions and generate a contact with God (Arutam).

The vision often is conveyed as a secret message by an ancestral spirit taking the form of an animal like a boa, a jaguar or an hummingbird. Not everyone obtains it immediately and the whole process might have to be repeated. These visions are seen as predictions of the future and will lead the warriors for the rest of their life. Knowing their future, warriors will have no fear in battles or confronting daily life.